The Box Office Keeps Disappointing. Indie Movie Theaters Keep Selling Tickets Anyway.

Second-run movies, rare film formats, Q&As and even Letterboxd accounts are helping independent cinemas bounce back faster from the pandemic than major theater chains.

By Ella Feldman

Edited by Greg David

2025 Capstone Project for Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY

The AFI Theater on a summer night in Silver Spring, Maryland. Photo by Mike Maguire via Flickr.

Over Thanksgiving weekend, Wicked: For Good and Zootopia 2 breathed some life into the box office, which had endured an exceptionally poor fall. But the hundreds of people who sat in an elegant art deco movie theater in Silver Spring, Maryland on Saturday evening weren’t there for either. They were about to watch Barry Lyndon, a three-hour film that came out in 1975.

Friend groups carrying popcorn and craft beer, couples on date night and dads with their teenage daughters scanned the theater for empty seats. Among the murmuring crowd sat Suli Paz, a 28-year-old film conservationist from Mexico City who had been waiting to see the Stanley Kubrick epic in a movie theater. “I never wanted to watch it on a TV,” Paz said. “I was like, this is the type of movie that I would like to watch on a big screen.”

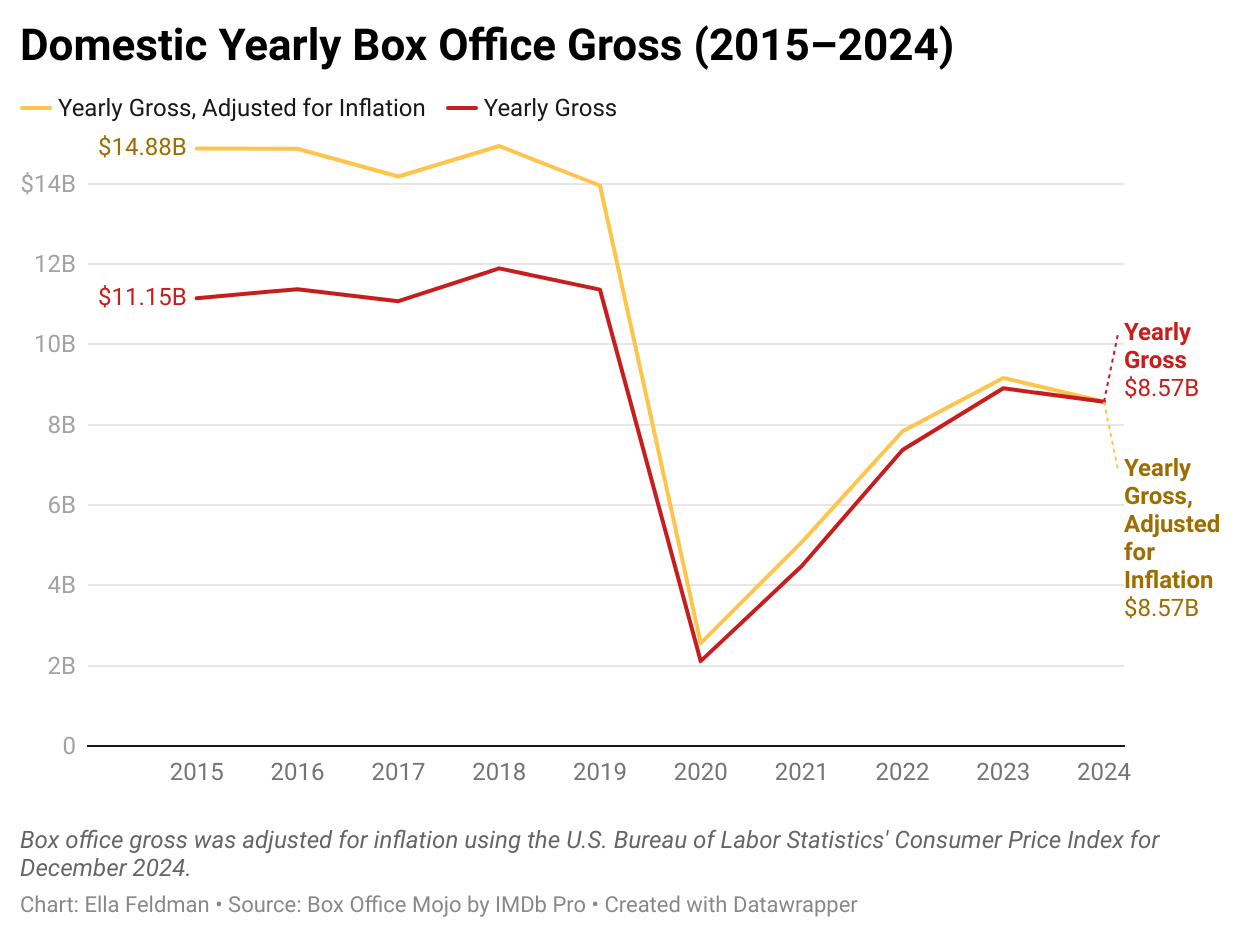

It’s been a tough five years at the box office. The dollar value of all tickets sold by U.S. movie theaters totaled $8.57 billion in 2024. That’s around three quarters of the $11.36 billion the box office grossed in 2019, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic forced movie theaters to shutter their doors. Adjusted for inflation, domestic box office gross declined almost 39% between 2019 and 2024.

The usual suspects for the box office’s woes include an explosion in streaming options, the writers’ and actors’ strikes and an overall decline in the quantity — and to some critics, the quality — of major studio releases.

Yet across the country, independent movie theaters have managed to buck the trend, according to industry data and interviews with theater operators. Major box office trackers like Comscore and IMDb’s Box Office Mojo don’t differentiate between major theater chains and indie cinemas when tallying up ticket sales. But according to Art House Convergence, an industry group for indie movie theaters, independent film exhibitors have recovered significantly quicker than the average movie theater. Between 2019 and 2024, per an AHC survey of 90 exhibitors, the number of tickets sold at art house cinemas in North America fell by 11%. Across all movie theaters, the dip was more than three times that, according to Statista Research.

“We strive very hard every day to make connections with our audiences, to build those relationships so that those folks do keep coming back,” said Kate Markham, Art House Convergence’s managing director. “They are invested in the cinema and we are invested in the audience.”

While the success of chains like AMC Theatres, Regal Cinemas and Cinemark Theatres depends greatly on whether Hollywood’s latest blockbusters can draw crowds, indie theaters exercise more programming flexibility. In the years after COVID-19 brought film production to a screeching halt, many indie cinemas have doubled down on repertory screenings, drawing crowds for movies that were released decades ago. They spruce up screenings of both first-run and repertory films with introductions by special guests, Q&As with filmmakers and carefully-transported 70-millimeter prints. As a result, some are doing better than ever.

That includes the AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center, the Maryland cinema that showed a 50th anniversary screening of Barry Lyndon in November. After a few years of steady post-pandemic recovery, the nonprofit theater matched its pre-COVID revenue in 2024. Their last fiscal year, which ended in June, was one of their best on record — and this one is shaping up to be even stronger.

This fall, the domestic box office had its worst October in nearly three decades as new releases like Tron: Ares and The Smashing Machine struggled to sell tickets. But the AFI Silver recorded its best October in history. The theater’s annual Latin American Film Festival, which showcases first-run independent movies from the region, reached record attendance, while repertory screenings of films like The Rocky Horror Picture Show and Suspiria filled up.

“If we were going to have our best year ever,” said Todd Hitchcock, the theater’s director, “it would start off something like this.”

Staying Alive

The Silver Theatre opened its doors in 1938, one of many opulent movie palaces that broke ground at the height of Hollywood studios’ vertical integration era. It operated on Silver Spring’s Colesville Road for decades, until the commercial district’s decline and growing pressure from home video made staying open unsustainable. The Silver Theatre closed to the public in the ’80s and sat vacant for years.

An effort to save the historic theater started to brew, culminating in the Los Angeles-based nonprofit American Film Institute, which had been exhibiting film in the D.C. area for years, acquiring the venue and reopening it in 2003. Today, the AFI Silver operates as a kind of movie theater that is succeeding across the country: a multiscreen nonprofit arthouse that brings foreign films, first-run independent titles, rare film prints and repertory screenings to a local audience willing to pay for them.

More than 250 movie theaters in the U.S. operate as nonprofit organizations, according to industry research group Cinema Foundation. As nonprofits, independent theaters can tap into donations and grants to survive, rather than relying solely on ticket and concessions sales.

When pandemic lockdowns forced movie theaters to close, some were never able to reopen. Since 2020, the country has lost over 5,000 screens, according to research group Omdia. That included some indie theaters, which faced the same challenges as everyone else. But those operating as nonprofits had an edge: They could access government funding such as Paycheck Protection Program loans and grants from the U.S. Small Business Administration, and ask their patrons for donations.

Indie theaters also found ways to reach their core audiences while maintaining social distancing requirements. Within two weeks of its pandemic closure, the Coolidge Corner Theater in Brookline, Massachusetts had set up a virtual screening room where people could pay to stream independent titles like Another Round and Bacurau.

Fourteen months later, the historic movie palace turned nonprofit opened back up and announced plans for a $14 million renovation and expansion, which it completed in early 2024. The renovation gave the Coolidge two more screens for a total of six, allowing it to cash in on growing demand. Last year, the theater sold 8% more tickets than they did in 2019, according to annual reports. It ended 2024 with a profit of around $392,000 on $7.67 million in revenue, according to their Form 990.

“We read the same articles that you've seen published everywhere that highlight the death of the cinemagoing experience, streaming this and streaming that,” said Mark Anastasio, who has been programming films at the Coolidge since 2007. “But we don't see any of that here. We are seeing more and more young people coming to the cinema and experiencing films the way they were meant to be.”

The Letterboxd Effect

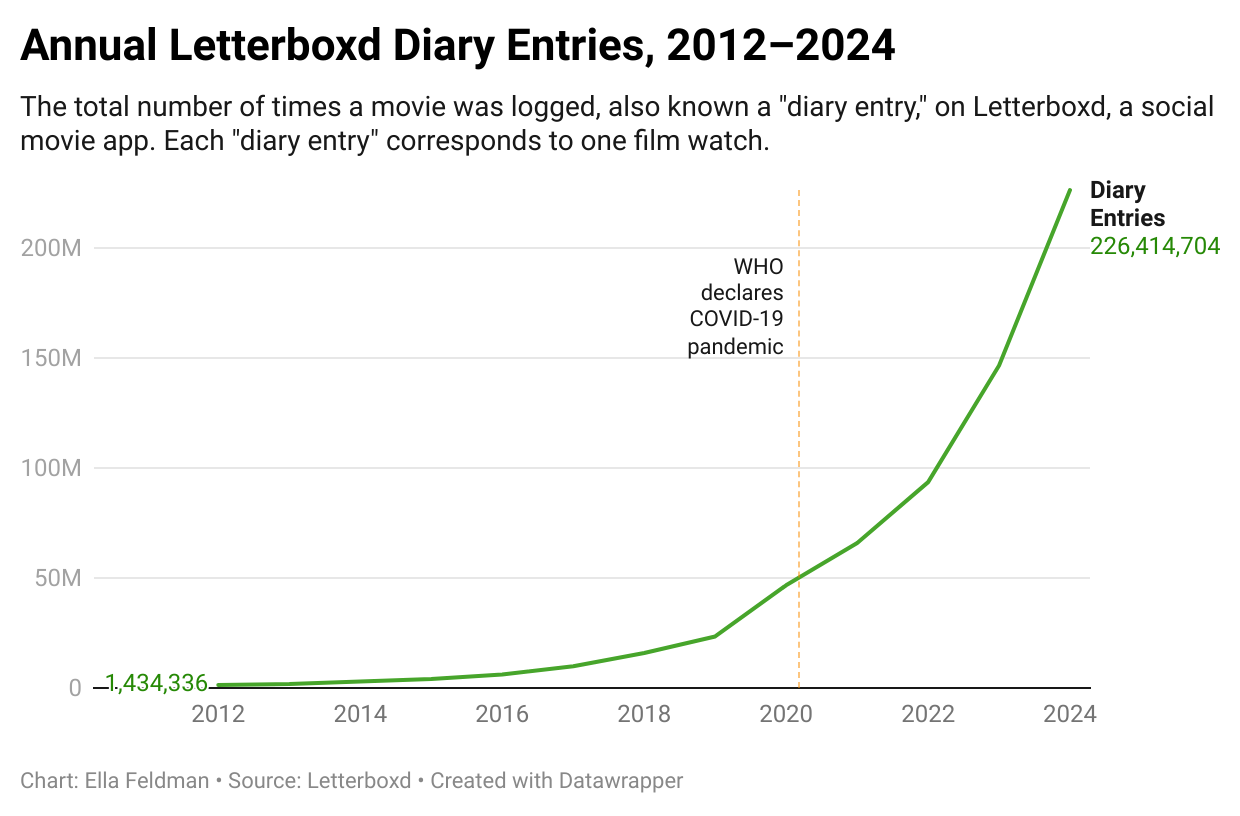

The pandemic may have decimated the box office, but it accelerated another way to watch movies: streaming services, which surpassed 1 billion global subscribers in 2020. For a generation of budding film lovers who were suddenly living at home and bored out of their minds, streaming during lockdowns became a gateway to passionate cinephilia.

Upon graduating college in May 2020 with a degree in screenwriting, Tajh Smith was supposed to move to Los Angeles to pursue a career in film. Instead, the now 27-year-old found himself unemployed and living at home in Brooklyn.

“During lockdown, I had nothing to do,” Smith said. “I would just watch a bunch of movies, like three a day sometimes. And then we’d want to categorize them and list them — I love making lists — and talk about them with my friends.”

That’s when Smith found Letterboxd, a website and app that lets users track every movie they watch with reviews and star-ratings. During the pandemic, the app became the internet’s watercooler for discussing film, almost doubling its reach. At the start of 2020, the website had 1.7 million users. As of early 2021, it had 3 million. The app has kept growing ever since. By the end of 2024, Letterboxd’s user base had surpassed 17 million.

Letterboxd inadvertently became a place where arthouses could reach their patrons, who sometimes tag reviews with information about the screenings they attend. Usually, after a repertory title plays the Coolidge, “a couple dozen people have hopped on to log about the experience that they just had at the cinema,” Anastasio said. The theater has its own account, where it shares information about upcoming programs with its 3,400 followers.

These days, Smith uses the app to keep track of all the indie theaters he frequents in New York, including the Film Forum and the Angelika. He makes sure to include whether he saw a special film print of a movie, like when he watched Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights on 35-millimeter film this summer at Brooklyn’s Nitehawk Cinema. “Cinema legit doesn’t get much better than this,” he wrote in his review.

Some film programmers suspect the app’s popularity has helped drive demand at independent theaters. Many indies have seen a strong showing from Gen Z in recent years, Markham said. The Coolidge, Anastasio said, is seeing “far and away a younger audience than we've ever had.” Twenty-somethings are showing up in greater numbers than ever at Portland’s Hollywood Theatre, according to head programmer Dan Halsted, as enthusiastic for Seven Samurai as they are for The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie.

Crowds are also trending younger at the Enzian Theater, a nonprofit arthouse in Maitland, Florida, said programming manager Tim Anderson. He suspects that following a year of social isolation, young people are itching for communal experiences. “I think it has to do with being cooped up,” he said. “If somebody's gonna save the movies, it's going to be people who are 20.”

At the Pickford Film Center, a nonprofit indie cinema in Bellingham, Washington, young audiences are driving demand for repertory titles. “My sense is that a younger generation is eager to discover older classics, classics they've seen on Letterboxd or on Criterion,” said Melissa Tamminga, the theater’s programming director. Criterion, a home video and streaming service, has a popular YouTube series where celebrities shop the company’s Blu-ray collection and discuss their favorite movies.

But the rise in repertory interest at the Pickford has coincided with a softening in demand for new-release arthouse and indie titles, such as The Shrouds, a David Cronenberg film that had its theatrical release earlier this year. “I'd be willing to bet we'd get a sold-out house if I programmed an event screening of Cronenberg's The Fly or even Crash or Videodrome,” Tamminga said, referencing the director’s older, cult-classic titles.

“It's an interesting conundrum,” she added. “I love that younger people are interested in older films. I'd love them to also be as passionately interested in more of the newer releases.”

Even the multiplex chains have started turning to cinema’s past. Fathom Entertainment, a joint venture owned by AMC, Regal and Cinemark that used to be known for bringing Metropolitan Opera performances to movie theaters, has leaned into repertory film programming in recent years. A 10-year anniversary release of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar in IMAX made $15.2 million domestically in 2024 during a two-week run. Last year, Coraline became the company’s most successful re-release in history, making $34 million domestically.

To Art House Convergence’s Markham, the increased number of repertory screenings at multiplexes is a sign that the big chains are taking a page out of the arthouse book.

“Something I find really interesting right now is that the multiplexes are like, ‘Hey, we should do retrospectives and we should do repertory cinema,’ which is something that indies have been doing very consistently for over a decade,” she said.

The Hollywood Theatre in Portland, Oregon. Photo by Darin Barry via Flickr.

Eventizing Cinema

Paul Dergarabedian has spent his career trying to make sense of the box office’s fluctuations. “It's like a game of whack-a-mole,” said Dergarabedian, a media analyst at Comscore who closely tracks the movie business. “Every time you think you've got it figured out, there's a trend or something that happens within the marketplace that changes our perception.”

That was certainly true in 2025. When Ryan Coogler’s original vampire story Sinners opened in April, some pundits got in hot water for saying it didn’t make enough of a splash on opening weekend to justify its $90 million budget. It went on to gross $280 million domestically, and was championed as a guiding light for Hollywood, proof that American audiences are willing to pay for original theatrical experiences. The following month, Lilo & Stitch made over $420 million, another sign that demand for movie theaters is healthy. Then, a lackluster summer followed by a disappointing fall left pundits scratching their heads.

Indie theaters can lean on repertory titles and special events when Hollywood films are flopping, but that doesn’t mean they’re immune to the box office’s twists and turns. When first-run titles from studios like A24 fail to catch on, it hurts arthouses. And when original, Oscar-bound movies for adults perform well at the box office, those same theaters sometimes find themselves particularly well positioned to reap the benefits — especially when there’s a specialty film format component.

During his press run, Ryan Coogler encouraged audiences to watch Sinners on film if possible. The movie was shot using a combination of large-format film systems, including IMAX 70-millimeter, which only eight screens across the country had the technology to screen. But a few indie theaters had the chance to screen non-IMAX, yet still rare, 70-millimeter prints of the movie.

“We've had ridiculous success with our 35- and 70-millimeter engagements,” said Hitchcock of the AFI Silver, which screened Sinners on 70-millimeter. “The public's got this idea of like, ‘You need to see it this way. That's the better way to see it. And yes, we will pay IMAX-type prices for it,’ that's been a huge part of our success.”

In September, Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another debuted to critical acclaim, quickly cementing its spot as this year’s awards darling. The film was shot on VistaVision, a rare format where 35-millimeter film is used horizontally. Only three venues in the U.S. were able to play the film in its original VistaVision format, including the Coolidge, which borrowed the necessary projection equipment from the George Eastman Museum.

“We really love playing film in its original format, or in the format it was shot in, whenever possible,” Anastasio said. “Thirty-five-millimeter and 70-millimeter are driving factors for audiences.”

Special film formats make going to the movies feel like an event, a way for theaters to “differentiate the movie theater experience from the in-home experience,” Dergarabedian said. “And that's really important, because why else would you go?”

Multiplexes are looking for ways to eventize, too. Last year, AMC pledged an investment to the tune of $1 billion into more premium large-format experiences, which the chain hopes will pay off by bringing in more audiences at a higher-price point.

Arthouses don’t have access to nearly as much capital as companies like AMC or Regal, but they’ve long found smaller ways to make cinemagoing an event, Markham said. “Whether it’s dinner and a movie, doing a craft at a family show, bringing in filmmakers to do Q&As or intros. Anything to make a screening particularly special is something that independent cinemas have been doing for a long time.”

‘We’ve Always Had to Pivot’

When news broke that Netflix had won the bidding war to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery in December, it rang out like a death sentence for the theatrical experience.

To many theater enthusiasts, the deal was a sour cherry on top of five years of failed post-pandemic box office recovery. The company that ushered in the streaming age of the 2010s is poised to take over one of the most storied film studios in Hollywood. Along with a major consolidation of entertainment options, critics of the deal are concerned it will only serve to tighten already shrinking theatrical windows, giving streamers a greater advantage over the theatrical experience and hurting cinemas across the country.

“Consolidation at this scale threatens the availability of movies on the big screen and the existence of independently owned theatres that serve their communities,” the Independent Cinema Alliance, a trade group for independent theaters, said in a statement.

It's a bleak prognosis. That’s not exactly new for indie theaters, which have weathered competition from home video, multiplexes, streaming services and more. Over time, many independent cinemas have buckled under the weight of those pressures, while others have found ways to survive despite them.

“Independent cinemas have always had to be scrappy, we’ve always had to pivot when these challenges have come up,” Markham said. “We’ve had to be really creative over the years to stay alive, stay sustainable. Even though the landscape is changing, it's not necessarily a death knell.”